10 reasons not to use bitdrift: 3, you like tools that were built for server apps

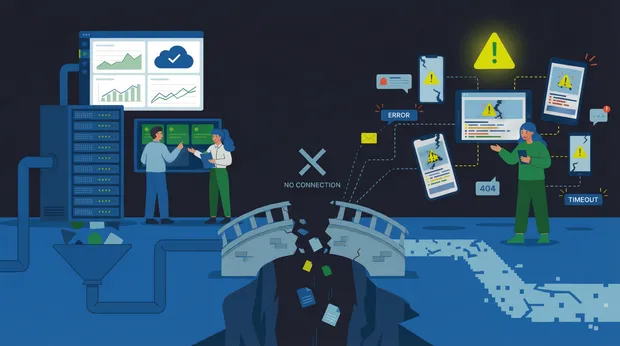

Continuing my challenge to come up with 10 reasons not to use bitdrift, this post explores why “full-stack observability” often means server-first observability. And why mobile dev teams pay the price for those assumptions.

When did we all become observability companies?

Once upon a time (not all that long ago), we had a smorgasbord of vendors offering a variety of tools to monitor application health: Log Aggregation, APM, Operational Intelligence, Web Application Monitoring, Digital Performance Management, Cloud-Native Monitoring … The list went on. Today, everyone is a “Full-Stack Observability” company. Or an Observability Pipeline, an Observability Cloud, a Centralized Observability Tool, a Single-Pane-Of-Glass-for-Observability, an Observability Tool Built for AI, an Intelligent Observability Platform … You get the picture. They’ve all got the “golden signals” covered; their agents and SDKs support every codebase, every flavor of hyperscaler, Kubernetes, and data source. So they all have Mobile Observability covered, right? Wrong. For years, mobile observability was effectively limited to crash reporting and a small set of pre-aggregated performance metrics surfaced by the platforms themselves. These signals were coarse, delayed, and detached from user context: no logs, no traces, no session-level visibility. As mobile apps grew more complex, existing observability vendors stepped in to fill the gaps, but they did so by extending server-centric models into environments they were never designed for. To be clear, many of these server-side observability tools are excellent at what they were built to do. It makes complete sense that teams would want to extend the same tools, dashboards, and workflows into mobile rather than introduce something new. Let’s dive into a few of the reasons why this approach doesn’t work.Mobile devices are not servers

It’s easy to think of each mobile device in your fleet as a tiny server sitting at the edge of your system. Just install an SDK in your app and start shipping telemetry to your legacy observability tool. But it’s not that straightforward. Every one of those “servers” runs a different app version and a different OS version on various hardware, under wildly different network conditions. In backend systems, that kind of variability is something you work hard to eliminate. On mobile, it’s unavoidable. And you can’t easily add logs or apply patches to an application that’s running on millions of unique mobile devices.Eventually connected

The moment connectivity isn’t guaranteed, server-side tooling starts to strain. Servers are built on the assumption that they’re always online. Mobile apps are not. Users walk out of Wi-Fi range. They move between cellular towers. They background the app halfway through a request. Sometimes the app is alive; sometimes the OS kills it without warning. From an observability perspective, this means data doesn’t arrive when it’s generated. Sometimes it arrives much later. Sometimes it gets dropped and never arrives. Server observability systems are designed for streaming data. Mobile telemetry is inherently delayed and out of order. That gap widens the moment you try to store mobile signals in time-series databases that were never designed to accept late data or reconstruct the past. If a device goes offline for ten minutes, the data from those ten minutes doesn’t neatly slot back into your charts when the device reconnects. In many systems, it’s either dropped or misrepresented. That is a fundamental mismatch. (We’ve written more about this exact problem here.)Observability is stealing your bandwidth

As teams add more instrumentation, another server assumption quietly sneaks in: network bandwidth is cheap. On mobile, it isn’t, and if you aren’t careful, the app itself can become the network bottleneck. Mobile apps are surprisingly chatty. They fetch configuration, poll APIs, upload analytics, send logs, emit events, and retry when things fail. All of that traffic competes with the actual product experience, especially on low-end devices and unreliable networks. One of our customers was able to determine, using bitdrift dashboards, that analytics and observability data accounted for more than 50% of all network requests and bytes sent by one of their apps. At that point, observability isn’t just something you pay for on a bill. It’s something your users feel directly in slower loads, higher data usage, and drained batteries. Server tooling was never designed with that constraint in mind.You don’t get a second chance to log

On the backend, observability can be iterative. You notice a problem, add more logs, deploy a fix, and try again. Mobile doesn’t work that way. Every instrumentation change requires a new release that the app store must approve. Users adopt new releases gradually, if at all. By the time your new logs are in the wild, the issue may have shifted, disappeared, or, worse, still be there, and you’re losing customers because of it. Server-first tools assume you can respond to unknowns after the fact. Mobile forces you to front-load observability decisions long before you know what will go wrong. So why not just log everything? You don’t just pay in dollars. You pay in CPU, battery, network usage, and performance. The inefficiencies that are merely annoying in backend systems become existential when they ship inside your app. For more on the challenges of mobile logging, see my previous post in this series.Hard-to-reproduce edge cases

Mobile apps are a factory for edge cases. Every user is running a different combination of device, OS version, app version, network type and quality, background state, battery, and memory pressure. That combinatorial explosion produces bugs that happen in a limited number of cases under just the wrong conditions. Reproducing these bugs is impossible. The only way to catch them is to log everything and capture every session. But on mobile, that simply isn’t feasible. Capturing full-fidelity sessions from every device would overwhelm networks, drain batteries, bloat storage, and degrade the very user experience you’re trying to protect. And yet, those rare edge cases are often the most expensive: support tickets, churn, negative reviews, and executive escalations. Server-side observability tools often miss these edge cases entirely. Sampling smooths away the p99 outliers, dashboards show “healthy” aggregates, and session capture (if it exists at all) is either sampled out or too low-fidelity to explain what actually happened. By the time an issue is visible, the session that mattered is already gone, and reproducing the problem locally is effectively impossible.Different assumptions, different outcomes

A mobile-native observability system starts from a very different set of assumptions.- Logs live on the device first, not the network. You can log aggressively without impacting users, because data doesn’t need to be streamed in real time.

- Connectivity is assumed to be bad. Sessions can span offline periods, Wi-Fi → cellular transitions, and delayed uploads, with backfill that reconstructs what actually happened.

- Logs are metricized and aggregated on the device. Instead of sampling raw events upstream, telemetry is pre-aggregated locally, enabling unsampled, real-time dashboards without shipping massive volumes of data.

- Observability can be configured and tuned at run-time. Configurations that target specific cohorts and edge cases can be pushed to devices in real time, without a code release, allowing mobile devs to collect full-fidelity sessions only when needed, without permanently incurring the cost across your entire user base.

Author

Iain Finlayson